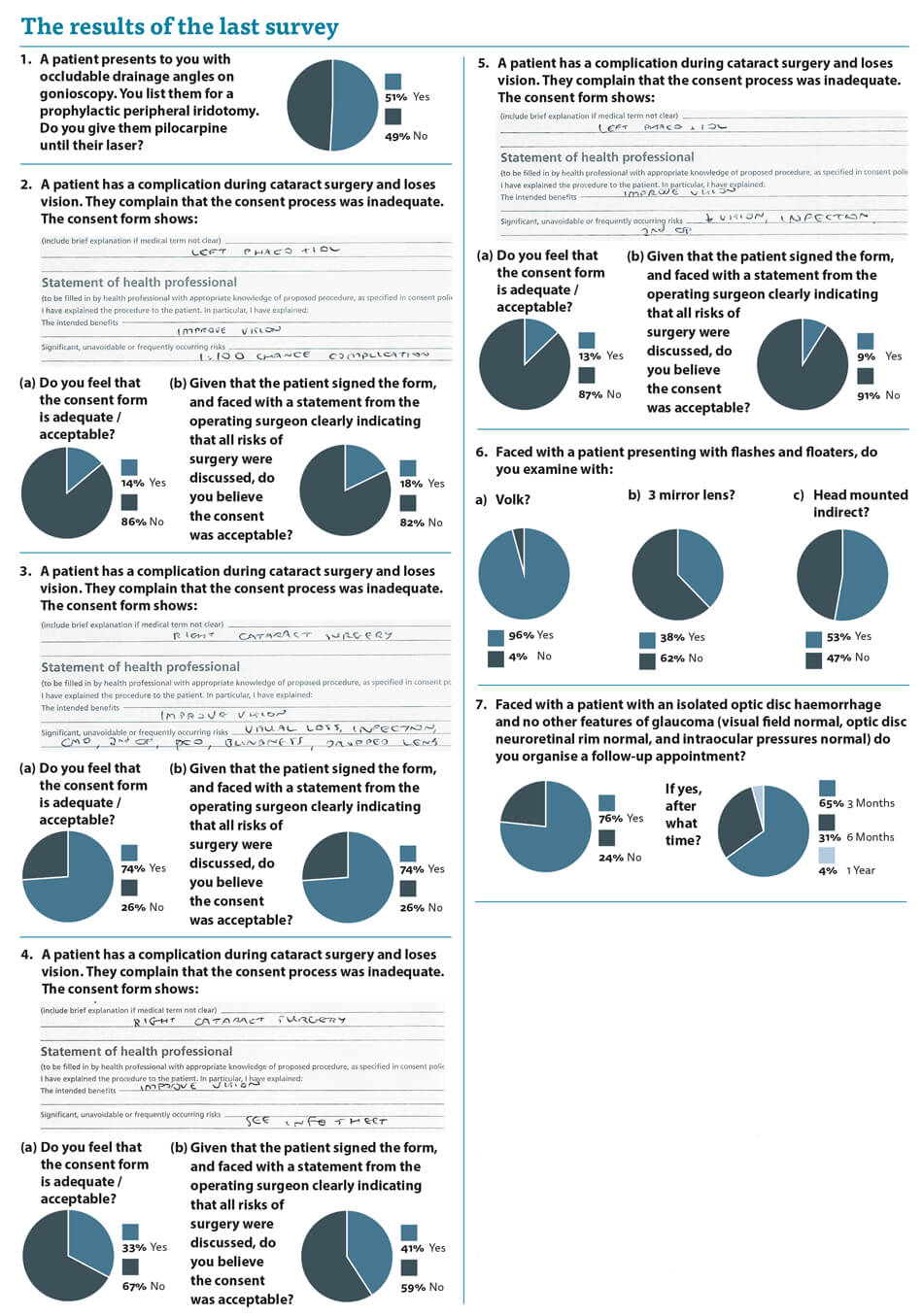

The responses to the first question in this survey demonstrate the need for it and the significant variation in practice we see in even relatively simple management decisions.

Patients are seen regularly with occludable drainage angles and listed for YAG laser peripheral iridotomy. It should be a reasonably simple question as to whether pilocarpine is given to miose the pupil with the aim of preventing mydriasis and precipitating acute angle closure. We have all been trained according to the same curriculum and we have all passed the same exams. Yet, despite this, we have an almost 50:50 split in the management of such patients. Half of us give pilocarpine and half do not.

So, faced with a patient who went into acute angle closure while waiting for their peripheral iridotomy and had not been given pilocarpine, would that patient have a reasonable grievance that they had been mismanaged? After all half of us give pilocarpine.

Who is right, the givers or the not-givers? I do not give pilocarpine as I fear precipitating the very pupil block which we seek to avoid. Should we have some consensus expert advice to guide us all in this?

The questions about consent are highly pertinent in the current climate, with more and more consent-related medico-legal claims against clinicians. I have spoken about consent before, but this time sought to put theory into practice and present you with consent forms and ask your comments on them. I have seen all these variants myself and am asked by the solicitors and the court as to whether they were reasonable. Remember that the consent process goes far beyond these forms and placing a signature on a document does not mean that adequate consent was obtained, however, these forms are presented as evidence and should give an indication of what was discussed.

The readership seems underwhelmed with the consent forms presented and only one of them (the one I actually use) gained any support. Even that consent form was deemed to be unacceptable by a quarter of respondents. It is clear that there is no support for consent forms with “see information sheet” and “1 in 100 risk of complications” so I would ask clinicians to stop writing this in isolation as it makes it extremely hard to say the consent process was adequate.

The examination of patients with flashes and floaters delivered results which were to be expected. I hope that patients are all examined with the Volk lens and either the three mirror or the head mounted indirect. My teaching was that the gold standard examination of these patients was head mounted indirect with indentation and yet I do not do that. Am I breaching my duty of care? I believe not. The real question is whether it is better for the patient for me to utilise a technique I was never particularly good at (head mounted indirect) even during my training and risk missing something or utilising a technique (three mirror) which I am happy with and I feel confident that I can detect the vast majority of significant peripheral retinal pathology. I believe the latter.

Regarding optic disc haemorrhages (ODH) we again see practice variation. Some clinicians do bring these patients back for review and others do not. Who is correct? The aetiology of ODHs is incompletely understood and no one knows why they really occur. I believe they are a reperfusion injury when seen in glaucoma eyes and we know that in normal tension glaucoma (NTG) they can be a manifestation of a stepwise progression. I like to bring these patients back at six months to see if there is any evidence of nerve fibre layer defect in the area of the ODH in case it is the first manifestation of NTG. Considering the lack of clinic capacity, answers and guidance as to what we should be doing would be welcome.

So rather than answering questions we once again are presented with questions, which hopefully those wiser than I can answer.

Comment from a glaucoma specialist

Andrew Tatham, Consultant Ophthalmologist, Princess Alexandra Eye Pavilion, Edinburgh, UK.

The results of the survey question regarding a patient presenting with “occludable drainage angles” indicate that if the patient was listed for a peripheral iridotomy 51% of responders would prescribe pilocarpine while the patient is waiting for the laser.

This is an interesting dilemma, and the best course of action probably depends on a patient’s individual risk. The term occludable drainage angles refers to primary angle closure suspect (PACS), an anatomical description of appositional closure of 180 degrees or greater on gonioscopy, in the absence of elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), peripheral anterior synechiae (PAS) or glaucoma.

The recent Zhongshan Angle Closure Prevention (ZAP) trial has shown that in Chinese patients with PACS, the risk of conversion to primary angle closure (PAC) is low [1]. The ZAP trial randomised 898 patients with PACS to laser iridotomy in one eye, while the other eye was untreated. Over six years of follow-up only 36 untreated eyes progressed to develop elevated IOP or PAS, and only five developed acute angle closure, suggesting that unless the waiting time for a laser is very long, prophylactic treatment with pilocarpine is probably unnecessary.

Whether the results of this study are generalisable to other populations is open to debate, but the study emphasises that when discussing treatment options, a patient’s individual risk factors and preferences must be taken into account. If considering prescribing pilocarpine, it is essential to discuss the sideeffects of cholinergic agents, including the frequent occurrence of headache, blurred vision and hypersensitivity, and the rarer sideeffects of corneal endothelial toxicity and retinal detachment. For patients living or travelling to remote areas, where access to healthcare may be limited, providing them with pilocarpine prior to laser would seem a sensible recommendation. However, for the majority of patients it seems reasonable to inform them of the symptoms of acute angle closure, and advise prompt medical attention if symptoms develop, along with advice to avoid drops for dilating pupils.

Question 7, related to the finding of an isolated optic disc haemorrhage. Optic disc haemorrhages are an important feature conferring increased risk of glaucoma and subsequent glaucoma progression. Patients with disc haemorrhages clearly need to be monitored over time to determine whether glaucomatous changes develop. However, depending on local arrangements, the optimum setting for follow-up will vary, and in many areas community monitoring will be most appropriate. In Scotland, national guidelines state that patients with isolated optic disc haemorrhages should be referred to the hospital eye service for a baseline evaluation but the majority of these patients are discharged at the first visit [2]. A recent publication found isolated disc haemorrhages had a low positive predictive value for glaucoma and almost 60% of patients with isolated disc haemorrhages were discharged to community optometry monitoring at the first visit [2]. With hospital eye services under increasing strain, and patients at high risk often having appointments inappropriately rescheduled, it is important that patients are stratified according to risk and that risk appropriate pathways are implemented.

References

1. He M, Jiang Y, Huang S, et al. Laser peripheral iridotomy for the prevention of angle closure: a single-centre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;10181:1609.

2. Hogan B, Trew C, Annoh R, et al. Positive predictive value of optic disc haemorrhages for open angle glaucoma. Eye 2020;34:2029-2035.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME