There was a really fascinating response to the last edition’s practice variance survey. Strictly speaking, I cheated and this was not really about practice variation, but more about your impressions about what represents negligent practice.

For the first time ever, we had a lot of respondents not answering a part of the question. This finding in itself is fascinating as it demonstrates how difficult the questions were to answer. The topics were complex and require a level of judgment which is not straightforward.

These sorts of issues are faced by medicolegal experts all the time and we are required to give an opinion on them which the Court will take into account. It should be emphasised that our role is to advise the Court and the ultimate decision on whether a clinician is negligent or not is the Court’s alone.

So how can we make a judgment?

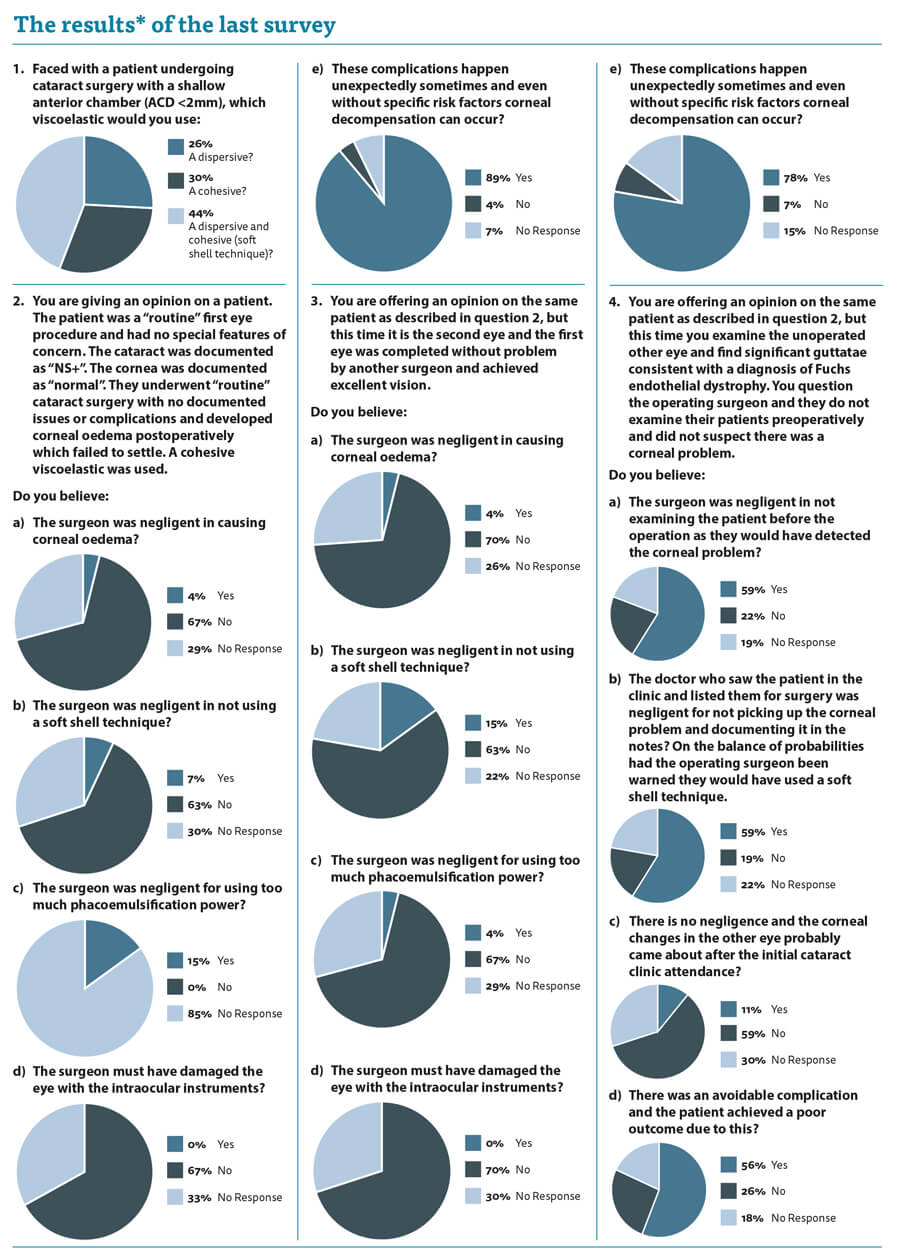

When I asked you, my learned colleagues, what sort of viscoelastic you would use with a shallow anterior chamber (AC), there was a relatively even spread between cohesive viscoelastic, dispersive viscoelastic or a mixture of both. Who is correct and can we really accuse the 30% of respondents who use a cohesive with a poor clinical outcome of negligence? Their conduct is supported by a reasonable body of medical opinion, so can they be negligent according to the Bolam standard? Furthermore, what if the medical expert is adamant that the way to do it is to use a dispersive viscoelastic and feels doing it any other way will cause problems and represents a breach of duty?

The questions left a lot of the respondents unable to give a definitive answer and I do not blame you. Without watching a video recording of the procedure or being there in person, how can we judge whether the conduct of the surgeon was reasonable? In the scenario I presented, we are faced with a patient with corneal oedema after apparently straightforward cataract surgery. It has certainly happened to me that a patient who I thought was routine and had uncomplicated surgery under me then developed corneal oedema postoperatively which failed to settle fully. Four percent of you feel that I am automatically negligent. Fifteen percent feel that I must have used too much phaco power. Thankfully, none of you feel I managed to directly traumatise the endothelium with my intraocular instruments. A lot of you wisely abstained and gave me the benefit of the doubt. Of note, 89% of you felt that these things happen despite our best efforts and I would tend to agree.

The rest of the questions and responses follow a similar theme, but I give more information to try and sway you one way or another. Despite my trying to tease you into coming off the fence many of you continued to abstain and again I cannot blame you. Such judgment calls are hard.

How can we judge surgical skills and competence of our colleagues? Procedures do not always go to plan, despite our best efforts, and I do not believe we should be fearful of the Sword of Damocles over our heads just because the outcome is not what we wanted. But equally, if our surgical skills are not up to muster then we should be called out and patients deserve compensation for poor surgery.

Whenever I am asked to assess breach of duty related to surgical technique I always caveat my opinion with a comment that I assume the surgeon has a level of competence which can be demonstrated by departmental complication and outcome audits.

How would our answers regarding potential negligence change if we knew that the operating surgeon had a post-cataract corneal oedema rate of 25%? Would this fact cause us to question their competence and skew us to a verdict of negligence?

It is vital that if we are to protect ourselves from allegations of negligence in our surgical technique that we robustly audit our outcomes and can present that data. Ideally, this should be done at a departmental level and form part of our regular appraisal and revalidation. It does not protect us automatically, however, if we genuinely mismanage a patient and make a surgical error, I genuinely believe we should put our hands up and allow the patient their compensation in the interest of justice.

*Please be aware that this data does not form part of a peer reviewed research study. The information therein should not be relied upon for clinical purposes but instead used as a guide for clinical practice and reflection.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME