Global eye health inequalities stem from poor access to affordable care, causing preventative vision impairment and blindness. In 2020, a study showed that 510 million people, the majority being in low-income and middle-income countries, had uncorrected near vision impairment simply because they did not have reading glasses [1].

Combine health inequality with political unrest and conflict, patients are further burdened with weaker health systems and increased morbidity [2]. Furthermore, vision impairment has substantial financial implications for individuals and their families. Reduced vision affects mobility, mental wellbeing, integration in society and can lead to increased need for social care in countries where the social care system is not robust [3]. This is a case report of a patient I had the benefit of meeting during my elective in Jaffna, Sri Lanka.

Figure 1: Diagram depicting the global eye health inequalities experienced in low- and middle-income countries.

These include, but are not limited to, poor access to affordable care, economic development, politic unrest and conflict.

Case report

A 42-year-old Sri Lankan Tamil woman presented to the Ophthalmology General clinic with reduced vision in the right eye and a left eye prosthesis. She had no other past medical history. She was a non-smoker, non-drinker and took no regular medications. There is no family history of ocular disease.

At the age of three, she had an ocular injury involving tree bark scratching the right eye. The patient did not seek medical attention post injury and was not symptomatic. Seventeen years later, during the peak of the civil war in Sri Lanka, the patient was injured by metal shrapnel to enter the left eye from a hand grenade balst. Due to the conflict, she only reached a field hospital three days post-injury. She was transferred to a district general hospital, where she was intubated and ventilated for 72 hours. After successful extubation, she had enucleation of the left eye and thereafter an ocular prosthesis, as shrapnel was lying adjacent to the left optic nerve. At this point, the patient for the first time, noted that the vision in her right eye was reduced, however, due to the lack of access to healthcare during conflict, the visual impairment was untreated. The patient has no documentation of the enucleation and did not have follow-up.

With the political tensions easing in Sri Lanka and with financial aid, she has been seen in a private ophthalmology clinic. Her clinic letter notes that her right eye has an untreated recurrent corneal ulcer likely from the corneal abrasion injury from her childhood, causing globally reduced vision. She was assessed to have best corrected vision in the right eye of 6/36 and was certified as a low vision patient, enabling her access to national government help in providing ocular aids. She has on-going follow-up to monitor her ocular health and assessment for further social support.

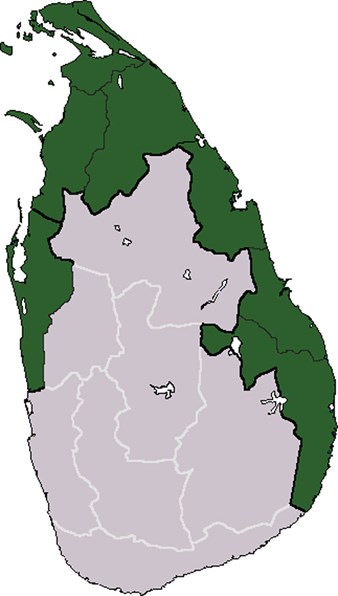

Figure 2: Map of Sri Lanka. The shaded green area showing where most of the conflict

occurred during the Sri Lankan Civil war. © QuartierLatin1968.

Discussion

Though Sri Lanka has a universal healthcare system, during the brutal 50-year civil war there was limited access to healthcare. This patient described the stigma associated with her ocular prosthesis. She feels her family is unable to integrate in society and has been shunned due to her disability. Furthermore, due to her poor vision, she cannot navigate in the dark and this impedes her ability to carry out activities of daily living. With a lack of electricity, once the sun sets, she is unable to do daily tasks – the main ones she described being helping her son with homework and getting the bus into town. This patient has suffered a preventative cause of vision impairment in the right eye which has left her with a poor quality of life. The patient now has reading glasses and a magnifying glass with an illuminating light. She can now continue with her day after sundown and feels her quality of life is better. This case highlights the importance of patients, especially in low-income countries, to have access to affordable healthcare to improve their morbidity and mortality.

References

1. WHO. World report on vision. 2019:

https://www.who.int/publications/i/

item/9789241516570

(Last accessed October 2021).

2. GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators; Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health 2021;9(2):e130-e143.

3. Koplan JP, Bond TC, Merson MH, et al; Consortium of Universities for Global Health Executive Board. Towards a common definition of global health. Lancet 2009;373(9679):1993-5.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME