Miller Fisher syndrome (MFS) is a rare, acquired nerve disease that is considered to be a variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome. It was first recognised by James Collier in 1932 as a clinical triad of ataxia, areflexia and ophthalmoplegia. Later, it was described in 1956 by Charles Miller Fisher as a possible variant of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS).

It is characterised by abnormal muscle coordination, paralysis of the eye muscles, and absence of the tendon reflexes. Like Guillain-Barré syndrome, symptoms may be preceded by a viral illness. Additional symptoms include generalised muscle weakness and respiratory failure. The majority of individuals with MFS have a unique antibody that characterises the disorder. We report a patient with MSF who presented with clinical signs suggestive of bilateral asymmetric globe retraction and negative ganglioside antibodies (anti-GQ1b).

Case

A 49-year-old male was referred to the ophthalmology department from the neurology team complaining of diplopia on right gaze which started one week ago. Suddenly, over a two-day period, he developed diplopia in all gazes, severe headaches – complaint of left eye being stuck in towards the nose. The patient had a flu infection about 15 days before the symptoms started. He was evaluated by the neurology team in A&E. He had no urinary / bowel incontinence. His past medical history was clear. He had no surgeries in the past. The family history was non-contributory. According to his past ophthalmology history he appeared to have only a normal refractive problem. He denied smoking, alcohol use, or drug abuse. He took no medication except paracetamol and naproxen. He had no occupational exposure to neurotoxins. He was found to have a slightly elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) protein of 0.63 and negative myasthenia serology. The rest of laboratory testing revealed normal results.

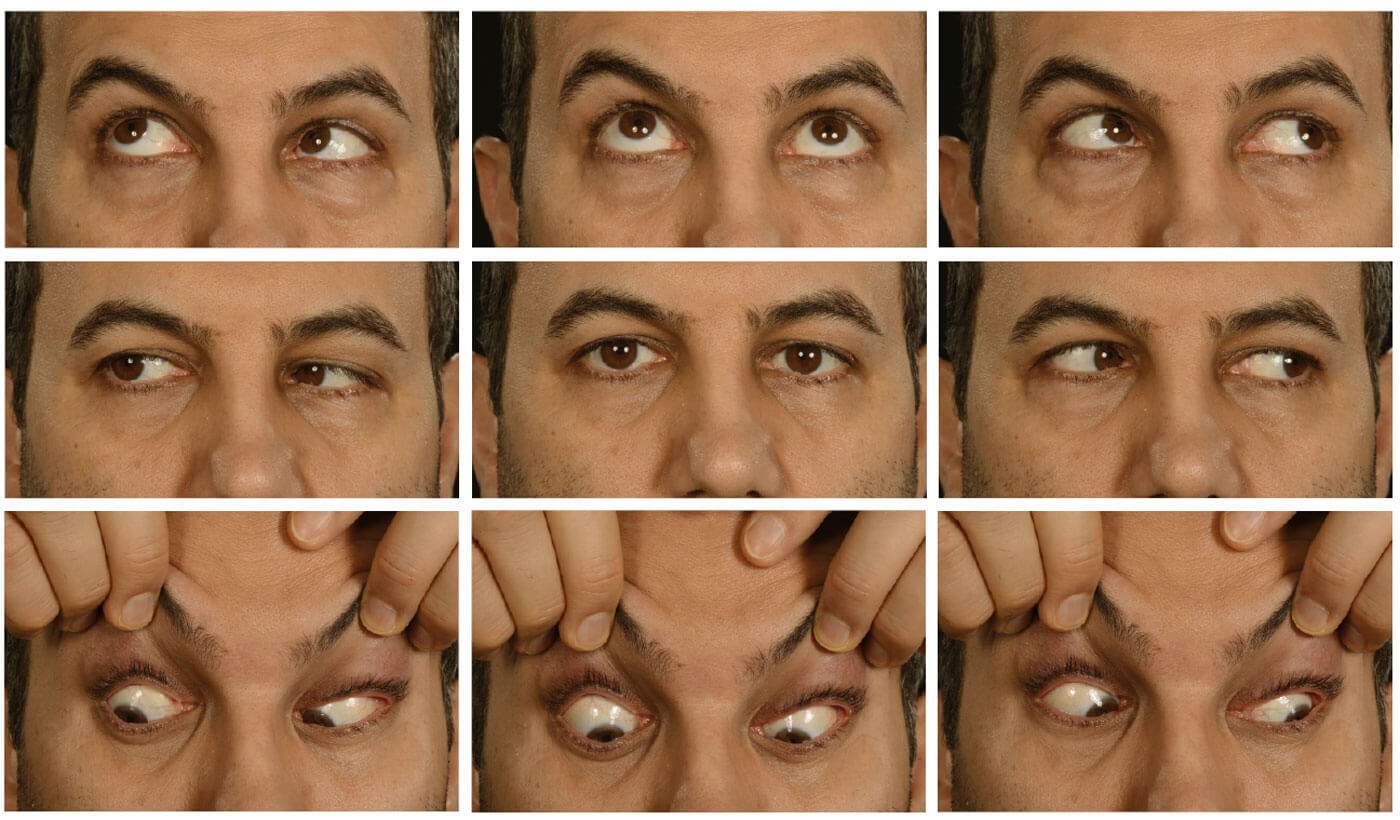

Looking straight ahead.

Looking straight ahead.

Looking far left.

Looking far right.

His right visual acuity (RVA) was 0.14(0.04ph) and left visual acuity (LVA) was 0.20(0.04ph). Both pupils were round, equal and slowly reactive to light. An orthoptic examination revealed globe retraction on adduction of either eye with narrowing palpebral fissures and left esotropia with diplopia. Prism cover test (PCT) measurements were 35 dioptres base out for near and distance fixation. An ophthalmology examination did not reveal the visual and retinal change. A five-day course of intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) treatment was initiated by the neurology team four days post orthoptic examination.

Day three of IVIg (one week after the first orthoptic examination): The patient complained of worsening of vision in the left eye but also felt as though vision in the right eye was reduced. He reported new shaking of arms and both legs over three days. His VA was good and stable bilaterally (0.00 unaided). New right abduction restriction was noticed and PCT measurements supported a diagnosis of right VI nerve palsy. The globe retraction was unchanged bilaterally.

Day five of IVIg: Double vision was unchanged. Bilateral globe retraction right >left, felt better and walking was more steady. PCT was slightly increased at 40 dioptres base out. His esotropia was found to be increased on right gaze (35 dipotres base out) in comparison to the left gaze (20 dioptres base out). Alternate occlusion on alternate days was advised. The neurology team referred him for ocular electromyography (EMG).

Five days later (two weeks after the first orthoptic examination): Overall symptoms are generally reported to be much better but no change to eye symptoms, still with constant diplopia with bilateral globe retraction, right VI nerve palsy, minimal vertical deviation (reversal on distance fixation). Overall function seems to be improving – no ocular changes noted. EMG test and conduction studies were normal.

One month later: A constant esotropia of the left eye remains in which he has slightly more reduced vision (due to a mild uncorrected refractive error). Minimal limitation of abduction in the right eye with an increased esotropia on right gaze. PCT unaided at near was 25 dioptres base out, and 35 dioptres base out on distance fixation. PCT on right gaze was 25 dioptres base out and 20 dioptres on left gaze. On direct elevation PCT was 15 dioptres base out and on direct depression 30 dioptres base out. The patient was able to maintain single vision till approximately 36cm and was still alternately occluding his eyes.

Three months later: He was reviewed by the neurology team and his eye problem was noted to be improving. No further orthoptic assessment was requested.

Discussion

Although MFS is a rare clinical entity to come across in the field of medicine, it holds clinical significance due to the list of differential diagnoses. The presenting symptoms of ataxia and ophthalmoplegia may confuse the clinician and suggest an upper motor neurone sign or central cause. The presence of additional neurological symptoms may confound the clinical diagnosis. However, thorough neurological, ophthalmology and orthoptic evaluation and the knowledge of such a rare syndrome can help to narrow down the differentials. This case emphasises the atypical presentation of MFS as unilateral ocular paralysis progressing to bilateral disease, which can mislead the actual diagnosis. It also signifies the importance of history taking and clinical examination as the diagnosis of MFS is mostly a clinical diagnosis of exclusion of other possible differentials.

COMMENTS ARE WELCOME