Halloween is a festival steeped in symbolism. Pumpkins, skeletons, ghosts and witches dominate the seasonal iconography, each representing broader cultural anxieties about death, darkness and the supernatural. Among these motifs, the eye, often depicted as glowing, disembodied or grotesquely exaggerated, occupies a distinctive place.

While less discussed than the jack-o-lantern or the black cat, the image of the eye has become increasingly common in Halloween decorations and popular culture. Incorporating an ophthalmological lens allows us to explore how the biological functions and pathologies of the eye amplify its symbolic resonance in folklore, art and modern horror.

The eye in folklore and myths

The concept of the ‘evil eye’ illustrates the long-standing belief that vision itself could transmit harm [1]. Anthropological studies show that such fears often emerged in agrarian societies where envy was thought to bring illness or crop failure [1]. From a medical standpoint, ocular pathologies, such as strabismus, are not only visibly distinctive but also socially stigmatised. Studies show that individuals with misaligned eyes often face negative perceptions of intelligence and moral character in media and are at increased risk of developing psychiatric illness [2]. These factors may historically have contributed to interpreting certain gazes as abnormal or supernatural [2]. The blending of medical abnormality with cultural superstition demonstrates how the eye became a liminal site between health and harm, natural and supernatural.

Eyes in the dark: animals and the ophthalmic uncanny

Pre-modern societies often feared glowing eyes at night, which were caused by the tapetum lucidum, a reflective retinal layer present in many nocturnal animals [3]. Cats, owls and wolves thus became entangled with witchcraft lore and demonology. From an ophthalmological perspective, this adaptation enhances scotopic (low light) vision, but culturally it was interpreted as a marker of otherworldly power. Halloween decorations that imitate glowing eyes in the darkness directly reproduces this physiological phenomenon, transforming a biological adaptation into a supernatural trope.

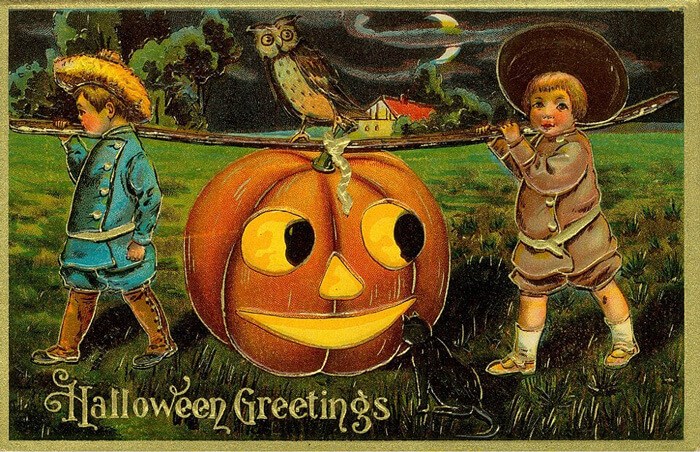

Figure 1: Halloween Greetings.

The eye in Halloween art

By the early 1900s, eyes, and in some cases anthropomorphic eyes, became common motifs in Halloween postcards, sometimes exaggerated for comic effect, as shown in Figure 1 [4]. This reflects both fascination with and discomfort about the organ of sight. At the same time, ophthalmological progress in the nineteenth-century, such as the invention of the ophthalmoscope by Hermann von Helmholtz in 1851, brought the hidden structures of the eye into view for the first time [5]. As medicine rendered the eye more knowable, Halloween art stylised it as uncanny and grotesque, suggesting a cultural counterbalance to medical demystification.

From ancient belief to modern horror

The evolution of eye symbolism demonstrates how cultural fears are reinforced by biological realities. The evil eye, once feared as a source of illness, now appears in playful Halloween decorations and accessories, such as trendy hairclips. Conversely, ocular pathology continues to inform horror aesthetics. Corneal leukomas, cataracts and subconjunctival haemorrhages, all of which alter the appearance of the eye, have been appropriated by horror films to signify monstrosity or possession, as can be seen in well-known franchises such as The Conjuring and The Exorcist [6]. Furthermore, pupils may also play a role in horror cinema, with dilated pupils often signifying terror, possession or intoxication; whilst pinpoint pupils evoke menace.

In horror cinema, the gaze has become central to storytelling. Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) used unblinking eyes as motifs of frozen terror, while The Blair Witch Project (1999) and Paranormal Activity (2007) explore the camera lens as a surrogate eye, transforming looking itself into a site of horror [7]. Ophthalmologically, the fear of being watched may resonate with the reality that vision is our most dominant sense, and damage to it is one of humanity’s greatest anxieties. Thus, the medical and symbolic weight of eyes converge in modern horror.

Figure 2: Bloodshot Eyeball.

Eyes in contemporary Halloween symbolism

Today, eyes appear in exaggerated, playful and grotesque forms. Oversized edible ‘eyeballs’ floating in themed drinks or cartoon ‘googly eyes’ in Halloween decorations parody ancient fears, as shown in Figure 2. At the same time, horror games and films continue to rely on eye trauma or disembodied gazes for visceral effect. Ophthalmologists note that direct injury to the eye is one of the most disturbing forms of bodily harm, eliciting intense aversion [8]. One might consider that perhaps Halloween’s recurring use of eyes, therefore, draws upon both cultural superstition and innate human discomfort with ocular vulnerability.

Conclusion

The eye is both a biological marvel and a cultural emblem, embodying humanity’s enduring awe, fear and fascination. Long described as the “window to the soul,” it is at once a means of perception and an object of scrutiny. From the evil eye of antiquity to the glowing gaze of nocturnal animals, from Edwardian postcards to modern horror cinema, its imagery has been shaped by evolving understandings of vision and ocular disease. These shifting representations capture our deepest anxieties about sight, surveillance and vulnerability. For ophthalmologists, Halloween’s recurring eye symbolism underscores not only the fragility of the organ we safeguard, but also its remarkable power as a lens through which to view culture, imagination and the macabre.

References

1. Dundes A. The Evil Eye: A Casebook. Madison; University of Wisconsin Press; 1981.

2. Liu J, Mantha A, Benjamin TD, et al. Depictions of Strabismus in Children’s Animated Films. Pediatrics 2024;154(6):e2024067355.

3. Schwab IR. Evolution’s Witness: How Eyes Evolved. Oxford University Press; 2011.

4. https://publicdomainreview.org/

collection/halloween-postcards/

5. Hirschberg J. The History of Ophthalmology. Bonn; Wayenborgh; 1982.

6. Skal DJ. The Monster Show: A Cultural History of Horror. New York; Faber & Faber; 1993.

7. Carroll N. The Philosophy of Horror, or Paradoxes of the Heart. London; Routledge; 1990.

8. Lin DJ, Lin SC. Ocular injury as a source of visceral disgust: Implications for trauma and horror media. Med Humanit 2018;44(2):93–100.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.