Central retinal vein occlusion (CRVO) is the second most common retinal vascular disease after diabetic retinopathy, and its clinical complexity often intersects with medico-legal scrutiny [1]. Missteps in timely diagnosis, inadequate follow-up or poor documentation can lead to patient harm and litigation.

To explore how clinicians manage key decision points in CRVO care, we conducted a survey amongst a group of resident ophthalmologists and specialist trainees in ophthalmology, at a tertiary eyecare centre, assessing their approach to common but high-stakes scenarios in retinal vein occlusion (RVO). This article highlights findings from that assessment and reflects on potential medico-legal implications supported by current clinical guidance and published evidence.

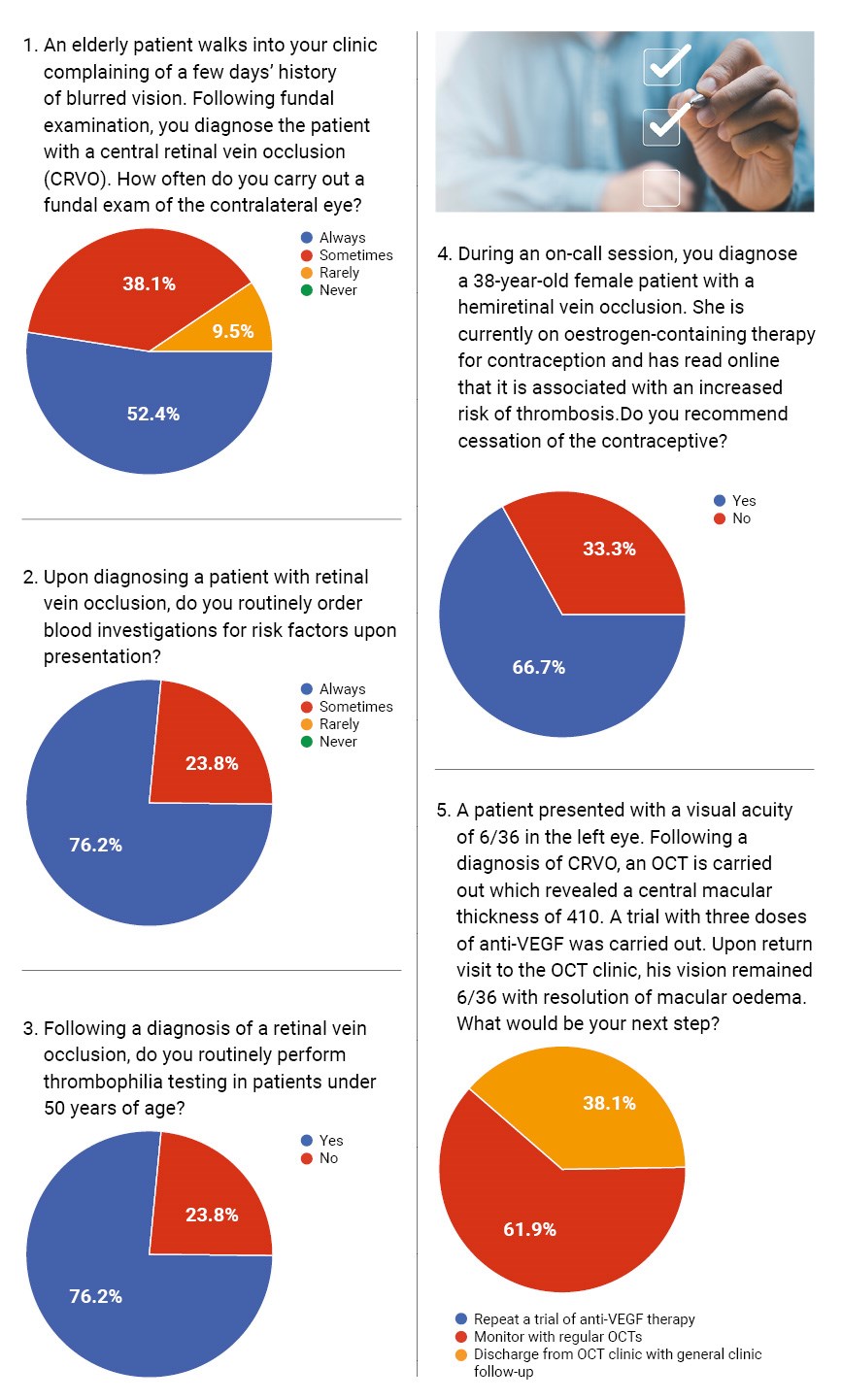

Often, CRVO reflects systemic vascular pathology that may affect both eyes. In our survey, 80% of respondents reported ‘always’ examining the contralateral eye when diagnosing CRVO, while 20% stated they did so only ‘sometimes’. According to the Royal College of Ophthalmologists (RCOphth), comprehensive fundal examination, including the unaffected eye, is essential in initial workup to detect signs of previous pathology, or bilateral disease, which may necessitate different systemic or ocular management strategies [2].

From a medico-legal perspective, failure to examine the fellow eye could delay necessary treatment or miss signs of systemic involvement. Inadequate documentation of this examination, or failure to perform it, could be grounds for negligence if the second eye later develops pathology.

All respondents reported that they routinely order blood investigations on initial diagnosis. This aligns well with clinical guidelines. Standard investigations include blood pressure, glucose, lipid profile, full blood count, and inflammatory markers [3].

In cases involving patients under the age of 50, 85% reported routinely requesting thrombophilia screening. Albeit younger patients are more likely to have underlying thrombophilic disorders (e.g. antiphospholipid syndrome), the British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BCSH) Clinical Guidelines for testing of heritable thrombophilia concluded that such testing is not required for RVOs [4].

Furthermore, literature has reported that CRVO patients and normal subjects had similar prevalences of inherited and acquired thrombophilia [5]. Hence, thrombophilia screening in young patients only leads to additional unnecessary costs and emotional burden on the patient.

We presented respondents with a case involving a 38-year-old female on oestrogen-containing contraception diagnosed with hemi-retinal vein occlusion. Sixty percent of respondents would recommend cessation of hormonal therapy, whereas 40% would not. This is a controversial area, but oestrogens are known to increase thrombotic risk, especially in the presence of additional risk [6]. Current best practice suggests a risk-benefit discussion with the patient, and where alternative contraception is feasible, cessation is often advised.

In a case where a patient’s macular oedema resolved after three anti-VEGF injections, but vision remained at 6/36, all respondents chose to continue monitoring with OCT. This conservative approach aligns with published findings that not all anatomical responses translate into functional improvement [7]. The RETAIN study supports continued observation in stable cases without macular oedema, even if vision remains impaired [8]. In such scenarios, legal risk is minimal provided the clinical reasoning is documented and the patient is informed of realistic visual outcomes.

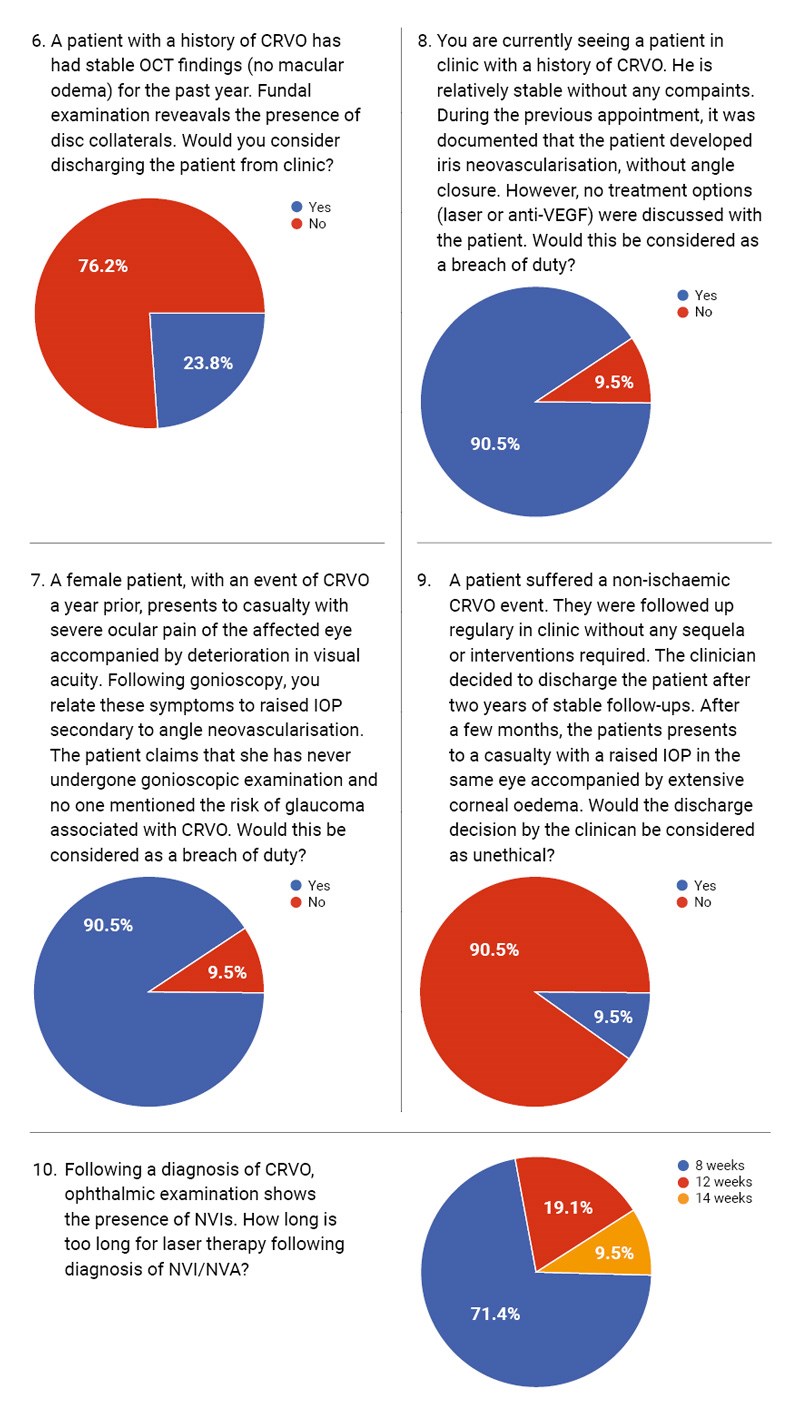

When asked whether they would discharge a patient with stable OCT and persistent disc collaterals, 80% responded ‘no’, preferring continued monitoring. Disc collaterals, though benign in appearance, may be associated with ongoing vascular instability [9]. The consensus appears to favour prolonged follow-up to detect late neovascular complications.

However, in a different scenario involving discharge after two years of stability in a non-ischaemic CRVO patient, all respondents agreed this was ethically justifiable. This shows clinicians often balance clinical risk against system pressures and capacity constraints. Medico-legally, the key is patient education at the time of discharge and clear documentation of stability criteria.

Two scenarios addressed complications related to neovascularisation. In the first, a patient presented with angle neovascularisation and claimed she had never undergone gonioscopy or been warned of the risk of glaucoma. All respondents agreed this constituted a breach of duty. Indeed, neovascular glaucoma is a known sight-threatening complication of ischaemic CRVO, and the Central Vein Occlusion Study (CVOS) recommends regular gonioscopic assessments within the first 6–12 months [10].

In the second case, no treatment was discussed despite documented iris neovascularisation. Again, all respondents flagged this as a breach of duty. The omission of laser photocoagulation or anti-VEGF therapy in such cases falls below standard care, and a lack of informed consent increases medico-legal vulnerability.

We asked clinicians how long is ‘too long’ to delay laser therapy after identifying neovascularisation of the iris (NVI) / neovascularisation of the angle (NVA). The most common response was eight weeks, consistent with RCOphth guidance which urges prompt intervention, ideally within two weeks from diagnosis, to prevent neovascular glaucoma. Delays beyond this point can result in irreversible damage and place clinicians at risk of litigation if the patient progresses to a painful blind eye.

This survey reveals that the assessed ophthalmologists largely align with evidence-based best practices in managing CRVO, particularly in systemic evaluation and recognition of neovascular risks. Nonetheless, areas of variation exist, especially in the management of hormonal therapy risk, discharge timing and communication of risks and interventions.

TAKE HOME MESSAGES

1. Always document contralateral eye findings and systemic risk work-up.

2. Ensure informed consent discussions around visual prognosis, treatment options, and systemic risks are thorough and recorded.

3. Discuss hormonal therapy implications in young female patients with vascular events.

4. Act promptly on signs of neovascularisation and avoid delays in laser or anti-VEGF initiation.

5. Patient education at discharge is vital – even when clinical parameters seem stable, always ensuring safety netting with adequate explanations of the ‘red flag’ symptoms.

References

1. Woo SC, Lip GY, Lip PL. Associations of retinal artery occlusion and retinal vein occlusion to mortality, stroke, and myocardial infarction: a systematic review. Eye (Lond) 2016;30(8):1031–8.

2. https://www.rcophth.ac.uk/resources-listing/

retinal-vein-occlusion-rvo-guidelines

[Link last accessed September 2025]

3. Hayreh SS, Podhajsky PA, Zimmerman MB. Natural history of visual outcome in central retinal vein occlusion. Ophthalmology 2011;118(1):119–33.

4. Tait C, Baglin T, Watson H, et al. Guidelines on the investigation and management of venous thrombosis at unusual sites. Br J Haematol 2012;159(1):28–38.

5. Romiti GF, Corica B, Borgi M, et al. Inherited and acquired thrombophilia in adults with retinal vascular occlusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Thromb Haemost 2020;18(12):3249–66.

6. Canonico M, Oger E, Plu-Bureau G, et al. Hormone therapy and venous thromboembolism among postmenopausal women. Circulation 2007;115(7):840–5.

7. Brown DM, Campochiaro PA, Singh RP, et al. Ranibizumab for macular edema following central retinal vein occlusion: six-month primary end point results of a phase III study. Ophthalmology 2010;117(6):1124–33.e1.

8. Campochiaro PA, Sophie R, Pearlman J, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients with retinal vein occlusion treated with ranibizumab: the RETAIN study. Ophthalmology 2014;121(9):1856–64.

9. Kolar P. Risk Factors for Central and Branch Retinal Vein Occlusion: A Meta-Analysis of Published Clinical Data. J Ophthalmol 2014;232(2):67–72.

10. The Central Vein Occlusion Study Group. Natural history and clinical management of central retinal vein occlusion. Arch Ophthalmol 1997;115(4):486–91.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.