*Co-first authors.

Myelinated retinal nerve fibres are retinal nerve fibres encased by a myelin sheath, located anterior to the lamina cribrosa [1]. First described by Virchow in 1856, a myelinated retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) appears as a whitish, feathery patch on the anterior surface of the retina that obscures underlying retinal vessels [2]. They are present in approximately 0.57–0.98% of the population and can be seen bilaterally in 7% of affected individuals [3,4].

Myelinated RNFL is usually asymptomatic, but can affect visual function depending on location, extent, and coexisting ocular pathology [3,5]. Because myelin can block light transmission to the photoreceptors, myelinated cause a relative scotoma, which is usually smaller in size than the patch of myelinated RNFL may suggest [1,4]. Ocular associations include axial myopia, amblyopia and strabismus [3-5]. Systemic associations include craniosynostosis, epilepsy, trisomy 21 and Turner syndrome [4,5].

Whilst typically benign, myelinated RNFL can be mistaken for other ocular pathology such as optic disc oedema, cotton wool spots, branch retinal artery occlusion, retinoblastoma, retinal infiltrates or leukocoria [1,6]. Thus, a comprehensive ophthalmological assessment is required to exclude more serious ocular pathology.

Myelinated RNFL is usually present at birth and non-progressive. However, acquired and progressive cases have been reported in childhood, adolescence and adulthood [7]. These include blunt trauma, optic nerve sheath fenestration, optic nerve glioma, optic nerve head drusen, neurofibromatosis type 1 and Gorlin-Goltz syndrome [1,7-10].

To the best of our knowledge, no published case has yet reported progressive myelination of the RNFL is in an adolescent following a horse-riding injury. Herein, we describe such a case and hypothesise potential explanations for this phenomenon, albeit we cannot be sure of the true pathophysiological mechanism. The patient has consented for this case report to be published.

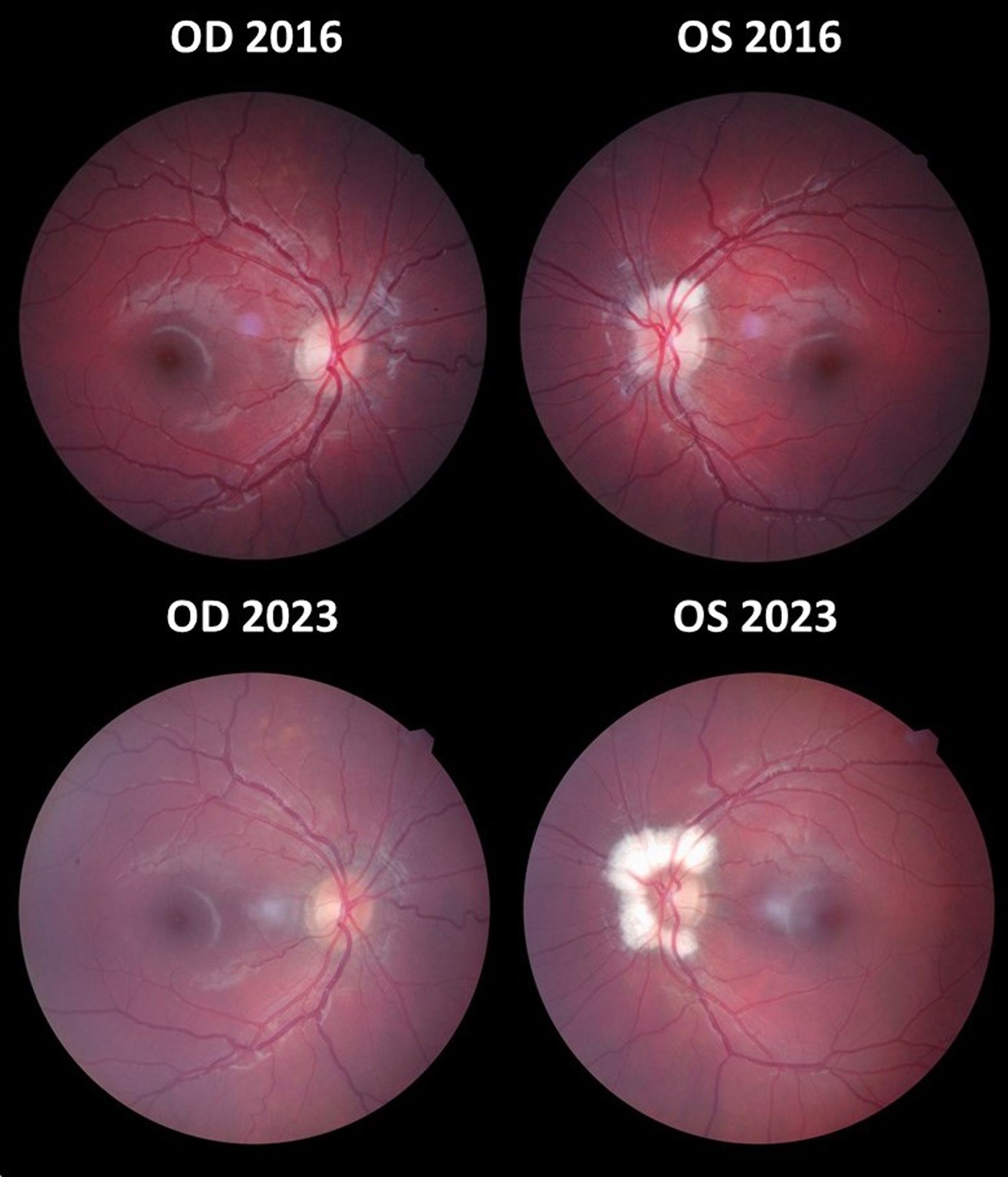

Figure 1: Fundus photography demonstrating increased myelination of the left optic disc.

Key: OD = right eye; OS = left eye.

Case report

A 19-year-old Caucasian woman was referred from her optician to our neuro-ophthalmology clinic for evaluation of progressive myelination of the RNFL. The optician first observed myelinated RNFL in the patient’s left optic nerve head in 2016, then referred the patient to our clinic in August 2023 after noticing a significant increase in myelination (Figure 1). Fortuitously, she had previously been seen by a senior consultant paediatric ophthalmologist in our ophthalmology department aged 18 months for right periorbital cellulitis, whereupon fundoscopic examination was recorded as normal in both eyes, including normal appearance of both optic discs.

She partakes in horse-riding as a hobby. She has no medical history of note, aside from falling off her horse in 2016 prior to her optician visit, whereby she landed in a seated position and sustained injury to her gluteal region and lower back. It is possible, though not definitively confirmed, that she may have experienced a form of ‘whiplash’ injury during the fall. Unlike the standard ‘whiplash’ injuries associated with road traffic accidents, this patient simultaneously experienced a vertical force transmitted through her spine on impact with the ground, as well as potentially an axial ‘whiplash’ force as her head came to a sudden halt, potentially causing a small breach in the lamina cribrosa.

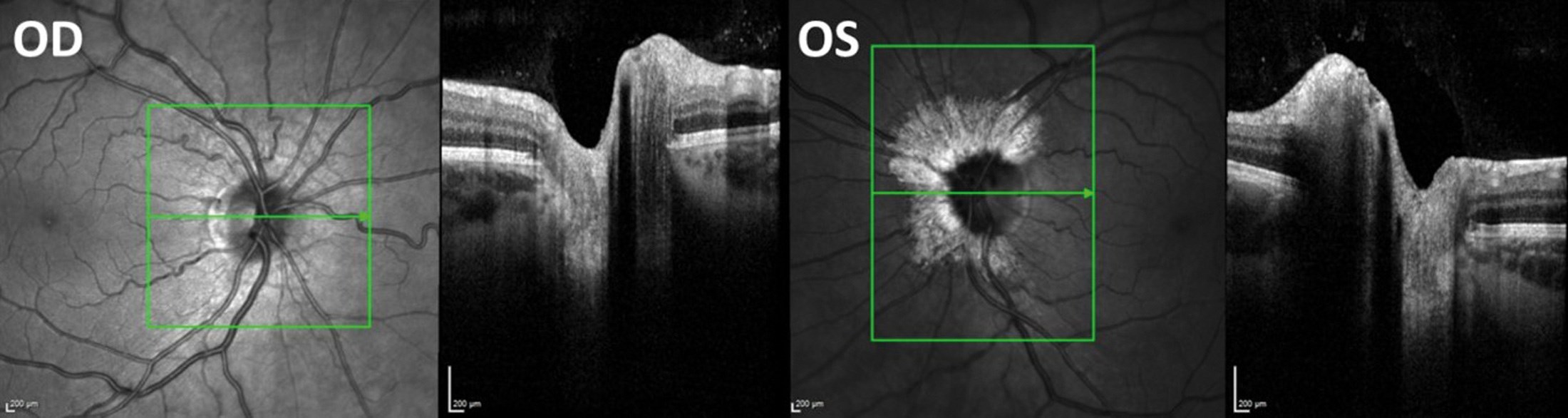

During our neuro-ophthalmological clinical assessment in August 2023, visual acuity was 0.10 in the right eye and 0.00 in the left eye. The patient reported no new visual changes. Intraocular pressure was 16mmHg in both eyes. Anterior segment examination was normal. Pupils were equal, round and reactive to light and accommodation. Dilated fundus examination of the right eye revealed a pink tilted disc with relatively small cup. Dilated fundus examination of the left eye revealed myelinated RNFL extending superiorly, nasally and inferiorly around the optic disc (Figure 1). Visual field testing using the Humphrey’s 24-2 model was normal in both eyes. Spectralis OCT imaging (Heidelberg Engineering, Heidelberg, Germany) was performed in both eyes, revealing myelination of the left RNFL (Figure 2); on infrared imaging, the myelinated RNFL appears white, most likely due to the high lipid content of myelin [4].

Figure 2: Infrared and OCT imaging of both eyes. Key: OD = right eye; OS = left eye.

Magnetic resonance imaging of the head and orbit was performed in July 2023. This demonstrated no acute spinal pathology. However, the central spinal canal appeared to be prominent. Following further discussion with the consultant neuro-radiologist, this was deemed to fall within normal limits.

We reassured the patient that no other ocular pathology was present, and the myelinated RNFL did not appear to be causing any visual problems. We offered routine monitoring; provided the patient is stable and happy, we aimed to subsequently discharge the patient back to her optician.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first published case of progressive myelination of the RNFs in an adolescent following a horse-riding injury. Whilst we cannot be certain of the precise aetiology in this patient, we have postulated three possible explanations: (1) the patient had normal, non-myelinated optic nerves since birth, evidenced by our senior consultant paediatric ophthalmologists’ examination findings when she was 18 months old, then her horse-riding injury caused her to developed acquired, progressive myelination of the RNFL; (2) the patient had subtle myelination of the RNFL since birth, which may have been missed on her examination at 18 months old, and the horse-riding injury exacerbated the existing myelination of the RNFL; (3) the patient had subtle myelination of the RNFL since birth, which have been progressive with age, entirely independent of the horse-riding injury.

Correlation is simply a relationship or connection between two phenomena, whether causal or not. Causation, or a cause-and-effect relationship, implies that one event directly causes another event. Correlation does not automatically imply causation, and we cannot definitively conclude that the horse-riding injury caused progressive myelination of the RNFs. All three possible explanations make various assumptions for which we have no definitive proof.

On balance, we think explanation 1 is slightly more likely, given that the consultant paediatric ophthalmologist who examined her as an infant was known to be meticulous, and thus unlikely to miss myelination of the RNFL. The consultant dilated the pupils and specifically examined her optic discs to exclude optic neuropathy, during her episode of preseptal cellulitis; they did not document any difficulty or limited patient cooperation during the examination. Furthermore, the myelination was never picked up on her optician visits until she was 13 years old, albeit she and her parents cannot remember her having dilated fundus examination during any of her prior optician visits. It is possible that the horse-riding injury may have caused a small breach in the lamina cribrosa, leading to progressive myelination of the RFL. Given that no fundus photography was performed when she was an infant, we cannot definitively conclude that the myelination was acquired; however, as demonstrated in the fundus photographs (Figure 1), we can conclude that the myelination is progressive.

The pathogenesis of myelination of the retinal nerve fibres is not fully understood. Oligodendrocytes are responsible for myelination in the central nervous system. The normal myelination process starts in vitro and ends at one month after birth [9]. Myelination of the optic nerve proceeds from its distal to proximal aspect, starting from the lateral geniculate ganglion and terminating at the lamina cribrosa [11]. Normally, the optic nerve loses its myelin sheath at the lamina cribrosa as it penetrates the globe. Myelinated RNFL results when myelination extends beyond the lamina cribrosa [1].

Whilst myelination of the RNFL is typically benign, its significant progression in this patient raised concerns during her optician appointment, hence the main purpose of the referral to our clinic was to exclude other ocular pathology. Following our neuro-ophthalmological assessments, we reassured the patient that she had no other ocular pathology, and all our findings were otherwise normal. Sharing this case report could help raise awareness and improve collective understanding of this phenomenon, which may be progressive following traumatic injury. Further work is needed to better understand the underlying pathogenesis of myelinated RNFL and associated ocular and systemic conditions.

References

1.Lyons CJ, Lambert SR (Eds.). Taylor and Hoyt’s Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus. 6th ed: Elsevier; 2022.

2. Virchow R. Zur pathologischen anatomic der netzaut und des scherven. Virchows Arch Pathol Anat 1856;10:170–93.

3. Kodama T, Hayasaka S, Setogawa T. Myelinated retinal nerve fibers: prevalence, location and effect on visual acuity. Ophthalmologica 1990;200(2):77–83.

4. Straatsma BR, Foos RY, Heckenlively JR, Taylor GN. Myelinated retinal nerve fibers. Am J Ophthalmol 1981;91(1):25–38.

5. Ramkumar HL, Verma R, Ferreyra HA, Robbins SL. Myelinated Retinal Nerve Fiber Layer (RNFL): A Comprehensive Review. Int Ophthalmol Clin 2018;58(4):147–56.

6. Shelton JB, Digre KB, Gilman J, et al. Characteristics of myelinated retinal nerve fiber layer in ophthalmic imaging: findings on autofluorescence, fluorescein angiographic, infrared, optical coherence tomographic, and red-free images. JAMA Ophthalmol 2013;131(1):107–9.

7. Jean-Louis G, Katz BJ, Digre KB, et al. Acquired and progressive retinal nerve fiber layer myelination in an adolescent. Am J Ophthalmol 2000;130(3):361–2.

8. De Jong PT, Bistervels B, Cosgrove J, et al. Medullated nerve fibers. A sign of multiple basal cell nevi (Gorlin’s) syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol 1985;103(12):1833–6.

9. Aaby AA, Kushner BJ. Acquired and progressive myelinated nerve fibers. Arch Ophthalmol 1985;103(4):542–4.

10. Parulekar MV, Elston JS. Acquired retinal myelination in neurofibromatosis 1. Arch Ophthalmol 2002;120(5):659–5.

11. Ali BH, Logani S, Kozlov KL, et al. Progression of retinal nerve fiber myelination in childhood. Am J Ophthalmol 1994;118(4):515–7.

Declaration of competing interests: None declared.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patient for agreeing to have this case report published. We would like to thank Specsavers Hinckley for providing fundus photographs (Figure 1).